I

My citizenship has always been a sensitive topic. I remember at university, I hated questions about my family background. Maybe this cornerstone is why I am such a private person. It is not apparent that I was born in the Philippines, not America, so I would gladly clarify that.1 But when the conversation veered to naturalization, there was warranted incredulity: after twenty years, how was I still not a citizen in this country, the United States, my forever home?

In my heart, I never knew the correct way to respond to this line of questioning. My instinct was to feign an upcoming resolution: I would say that my green card was coming next year if some handwaved complications were resolved. Next year would come, and without fail, the complications continued. They would always continue; the complications of this limbo state — this “status purgatory between permanent resident and unwanted non-citizen”, as I have exhaled before — are the essence of my immigration status. I am undocumented.

The brand was a stigma, though not of my own doing. There’s a scene in Westworld that describes this sort of trauma. The Man in Black (Ed Harris) explains his individual burdens and the darkness in his soul: “No one else sees it. This thing in me. Even I didn’t see it at first. Then one day, it was there. This stain, invisible to everyone.” I find it precisely parallels my feelings. When did this rage, this sadness come over me?

In 2012, I was granted temporary permission to stay in the country, through a policy known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). By meeting the qualifications for the program, I was granted prosecutorial discretion, meaning that deportation proceedings would not be taken against me during this temporary period. This temporary permission was granted in increments of two years, with the possibility of renewal.

Former President Obama gave relevant remarks regarding my family’s situation and how we came to be undocumented. At the 2016 Asian Pacific American Institute for Congressional Studies Awards Gala, an event my sibling was invited to attend, he introduced my sibling, explained my family’s background, and discussed the implications of DACA. I am still in awe that these words were spoken:

So I want to tell Regina's story, because it's an example of what's at stake here. Regina came to the United States from the Philippines when she was five years old. But when her father, who was an engineer, fell ill, he had to give up his job — which meant he could no longer secure documentation for his family. So Regina’s mom supported the family by working at a hair salon. Regina grew up as American as anybody else — she didn’t even know until she was in middle school that she was undocumented. And she didn’t understand until then that she’d be perpetually in danger of being deported from the only country she had ever called home. As a junior in high school, Regina requested relief under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals — or DACA — policy that we put in place. And today, she’s a sophomore studying economics at the University of Maryland. Her future is bright, and America is better off because she is here. That's the story of immigrants in this country.

It is 2022. My mother and father continue to live in their humble means. My sibling and I have long since left college. I have worked in San Francisco as an engineer; they went to graduate school before returning to Washington D.C as a policy analyst. We are living how our parents wanted.

It has been a decade since DACA was first announced. I still file for renewals for my temporary permission. It reminds me of my anger, my darkness, my pain. I feel guilty for wanting more: I want the last piece of my family’s dream. I want to be a citizen.

II

There is no Golden Path, no “Secher Nbiw” to citizenship for undocumented who have entered the United States as minors; however, the undead idea has been entertained: the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act does just this. The legislative proposal was first introduced over twenty years ago in 2001, yet it remains in the state of its acronym: a dream. Variants of this proposal continue to be struck down or lost in the Senate. The most recent iteration, the U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021, is Biden’s attempt at the matter, in homage to a long-standing campaign promise.

Of course, as a potential pathway to citizenship attempts to stand, retaliation comes in the form of destroying the floor that supports it. The most egregious case came in 2017. Unbelievably, the floor held. But the floor continues to be questioned for its imperfections. As of recent, one hopes that the demolition plans will finally halt, but history has shown that this hope is not lindy.

No matter. The undocumented need not fear paths without guarantees. We have lived on them for our entire lives.

There are alternatives. According to CitizenPath, there are four conditional options that can grant lawful permanent residence:

Marriage to a U.S. Citizen or Permanent Resident

Green Card Sponsorship through Employment and Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) 245(i) adjustment with Legal Immigration Family Equity (LIFE) Act Protection

Asylum Status

U Visa for Victims of Crime

I want to focus on (2). In fact, this is the process that I am currently going through. In this Kafkaesque intersection of complex immigration law, I have found the gate before the law. The path’s absurdities inspired doubt in its seemingly theoretical linkages of legal code. Kafka speaks to me, through his gatekeeper, about the nature of this Amigara Fault entrance: “‘Here no one else can gain entry, since this entrance was assigned only to you.’”

In Kafka’s parable, the recipient of the gate dies before he receives his desired permission to be let inside. My case is the opposite: I have been given permission by the gatekeeper. Before we go in, let me explain this gate.2

III

A common process that foreign workers undergo for lawful permanent residence is through an employment-based petition. This is usually done after receiving an approved employment-based, non-immigrant, visa (e.g. H1B visa) to enter the U.S. and work for a U.S. employer. This bridges the temporary status from the non-immigrant visa with the permanent status provided by the immigrant visa.

There are three main steps in this process:

Program Electronic Review Management (PERM) Labor Certification

I-140 Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker

I-485 Adjustment of Status

The labor certification essentially ensures that the employment-based petition attests to a couple of qualifications. The job offer must be legitimate and meet minimum prevailing wage requirements based on the job requirements and location of employment. The job should not adversely affect U.S. workers. The job offer must be tested in the U.S. labor market to ensure that no qualified U.S. workers were available for the position.

Afterward, the I-140 petition is filed to verify that the foreign worker meets the requirements of the job described in the labor certification and that the sponsoring employer can indeed pay the specified wages. When this petition is accepted, the foreign worker receives a priority date, a marker indicating the position within the green card queue.

Every month, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) updates its Visa Bulletin charts, which indicate the threshold of priority dates for applications that are eligible for processing. Once the foreign worker’s priority date is current, then the worker is eligible to file the I-485 form to adjust status.

Ok great. What’s the catch?

Unfortunately for the undocumented, there is a notion of unlawful immigration status. When my family overstayed our initial visa, we now were classified in this category. According to the USCIS, “[an] applicant is barred from adjustment of status if the applicant is in an unlawful immigration status on the date of filing the adjustment application.” DACA does not confer legal immigration status.

There are consequences for the accrual of this unlawful immigration status: if you leave the U.S., you will not be able to re-enter for three or ten years, depending on the length of your unlawful status.

Those in this situation are caught in absurdity. To adjust status in this predicament, one must leave and legally re-enter the country to get back into lawful immigration status. But then, you’ll be caught with the re-entry ban hammer. There is no win.

Unless?

Enter Section 245(i). There is a wonderful summary about this immigration law, as explained by Andrew Moriarty, Deputy Director of Federal Policy at FWD.us. The context behind this law is worth quoting in its entirety:

Congress created Section 245 as part of the initial INA in 1952 to provide certain individuals admitted to the U.S. as nonimmigrants (such as temporary workers or international students) an opportunity to adjust to permanent lawful status without having to first leave and reenter the country, so long as they are otherwise eligible to receive a green card and one is available. This allowed individuals who were already living in the U.S. to stay with their families and continue working while they completed the immigration adjustment process.

Initially, only individuals who were lawfully admitted or paroled into the U.S. and had maintained lawful status could adjust under Section 245. In 1994, Congress added section (i), extending eligibility to certain undocumented immigrants who were not lawfully admitted to the U.S., who were employed without authorization, or who were not in lawful status at the time of applying, so long as they had a valid petition filed on their behalf before the filing deadline.

Section 245(i) became particularly important after the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (Pub. L. 104–208) was implemented in 1996. This act imposed severe penalties on individuals who were present without authorization in the U.S., including barring them from reentering the U.S. for many years after departing. These reentry bars created a significant barrier and disincentive for undocumented immigrants to leave and attempt to reenter in a lawful status. Adjustment under Section 245(i) protects individuals from having to go abroad to secure a green card, and thereby from triggering the bars that would keep them stuck abroad if they could not get a waiver. It also preserves a realistic pathway to correct unlawful status.

In short, this section of law has the potential to address the absurdity when undocumented adjust status. They just need a valid petition filed on their behalf before the section’s filing deadline. This hidden eligibility can make all the difference.

Initially, this filing deadline was October 1, 1997. The deadline was advanced multiple times. Eventually, the deadline was advanced to April 30, 2001. Again Moriarty shares the necessary context:

The passage of the LIFE Act in 2000 advanced this filing deadline again to April 30, 2001, and expanded access to many other categories of immigrants previously excluded, but added the requirement that the individual be physically present in the U.S. on December 21, 2000. Congress has not advanced the date since.

My initial petition as a dependent of my father fits all of these requirements and there are documents to prove his physical presence on December 21, 2000.

My current employer is filing an employment-based petition on my behalf. Once I am ready to file my I-485, I can use my initial petition to adjust my status under Section 245(i).

Thus, here I stand before the gate.

IV

I think about luck in the discovery and implementation of this process.

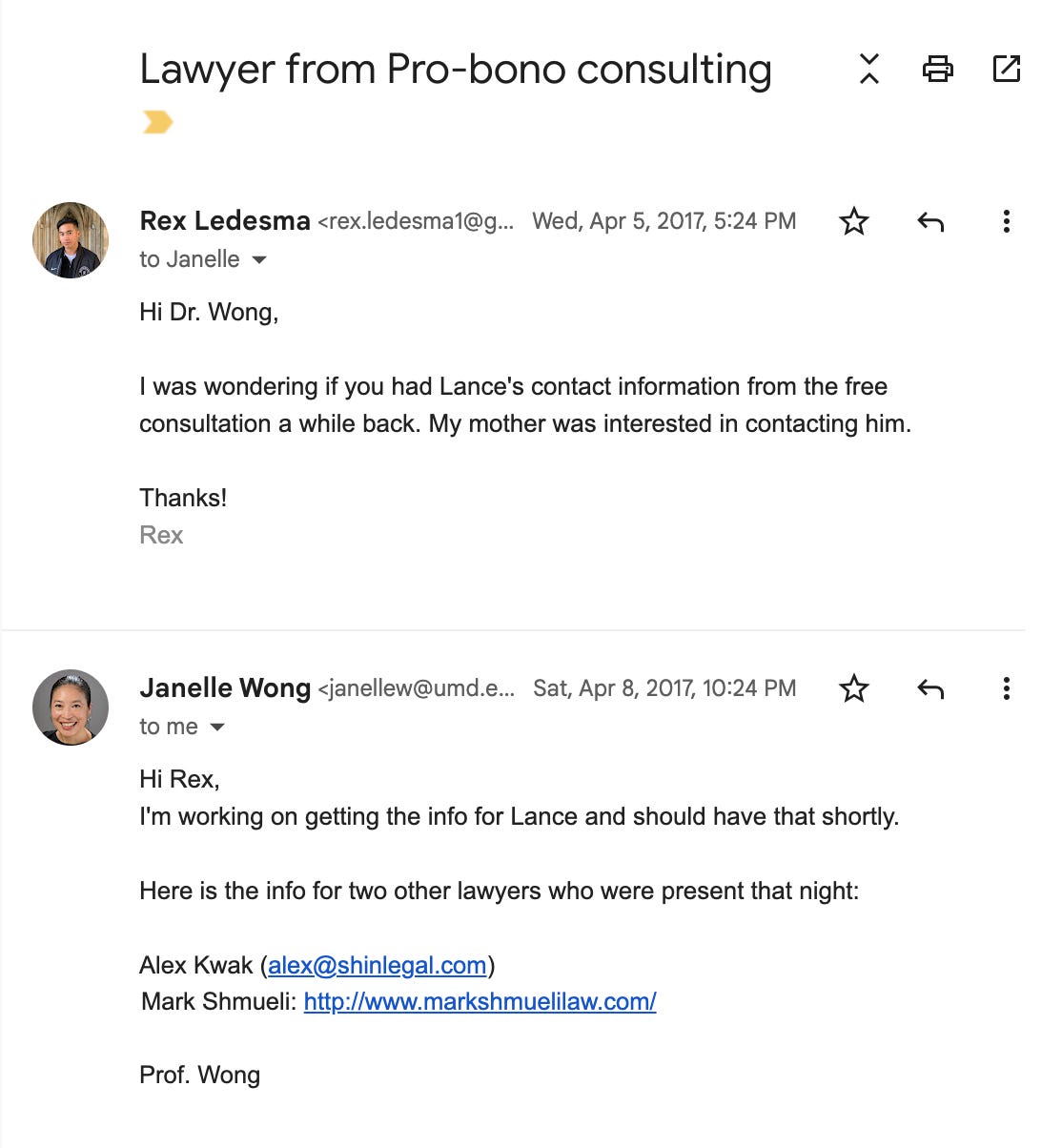

I discovered my current pathway when I was still attending university. On March 2017, at a pro bono consultation session sponsored by the Asian American Studies Program, I was explaining my circumstances to one of the lawyers, Lance. He opened my eyes to the possibilities, though it was still unclear, still so intangible. Was this really the case with my situation?

The same month, I flew out to Silicon Valley for the first time to interview for a software engineering role. I was declared bioengineering at the time, and I was still unsure what I wanted from my studies. I had already applied to transfer out of Maryland, to find a new direction, wherever it may be.

That flight changed my mindset. I wanted to chase the idealism, that sense of innovation from the west coast. In the subsequent semester, in my third year at university, I shifted all my coursework to mathematics and computer science. I continued my studies at Maryland.

Only in hindsight was it clear that both my realizations were functionally aligned. Without them, my pathway before the law would remain in theory, unable to be acted upon. My experience in the technology sector set me up to be a strong applicant for an employment-based petition.

There is another memory I have about luck. I received a scholarship back in 2010. To celebrate the newest recipients, the scholarship foundation hosted a reception in Washington D.C. At the event, when I went to go sit down at my table, one of the educational advisors from the foundation congratulated me on my achievement. You are so lucky, she mentioned. The foundation’s executive director at the time, Lawrence Kutner, was right beside me. He immediately interjected, “It is not luck. It is skill.”

There is a culture of individualism, of self-sovereign control, rooted in that statement. That it was all in my power to make myself. It is no surprise that the foundation’s motto is “Think Big. Work Hard. Achieve.” There was a time when I truly believed in this narrative, but now I am not so idealistic. There are caveats to acknowledge. It does not make one weak.

It is without a doubt that I have underestimated the impact of luck in my situation: that this pathway exists in the first place, that my father’s original documents just match up in accordance with the law, and that DACA was instituted and defended. It makes me sick. I feel so much weighing on this.

I do not practice numerology, but this entire ordeal makes me question myself. Is this my meta angel?

V

When I think about defining moments in my life, my thoughts shift back to graduating in 2019. I wrote this back then:

We are our parents’ dreams. After eighteen years marked with financial hardship, immigration woes, and periods wrought with immense emotion, it is against all odds that this moment exists. This is our family’s moment, the realization of a classic dream of Filipino immigrants in a new world. My father and mother gave up their world to give us ours. I’ll ensure that such a sacrifice is not in vain.

To all who are my family, tied not by blood but by our love and shared strength, thank you. This moment is here because of you as well. We have truly been showered from blessings above to support us on this long journey. This moment has been a long time coming. I’m proud of us.

The journey has taken me to this gate. I am about to enter it. I know what lies after. It is so close.

Though, if I open the lights, will my statement guide your intuition?

Obligatory “I am not a lawyer, this is not legal advice.”